"I read somewhere that 77 per cent of all the mentally ill live in poverty. Actually, I'm more intrigued by the 23 per cent who are apparently doing quite well for themselves."

—Jerry Garcia 1942 Ð 1995

"If one were to closely analyse the behaviours of all living things, we would find we all exhibit some form of mental illness. It is just that some people are good at masking it than others while others are use to the behaviours as they too do the same things as everyone else."

SUNRISE

The risk of unbalancing our thinking

What if we do not allow the brain to properly balance itself over time (i.e. the point where both hemispheres are well-developed and able to control each other with the help of the frontal cortex and the corpus callosum) and then, for whatever reason, perhaps due to insufficient time or other restrictions (in what we call limited support or other forms of poverty), our brain is suddenly forced to reverse the flow of a large amount of information from the L-brain to the R-brain or vice versa in a very short period of time? Can this permanently damage our brain?

The research conducted at SUNRISE is suggesting this might be true. There is evidence to suggest such imbalanced behaviours, if taken to the extreme by genetics or the environment, can result in what psychologists call mental illness.

Understanding mental illness in the 21st century

Mental illness is an insidious disease of the mind affecting literally tens of millions of people around the world. In Australia alone, with a population of around 18 million, it is claimed that approximately 20 per cent of the Australian population are or will suffer some form of mental illness.

In the United States, the estimated number of people who meet the latest criteria for mental illness is now 44 million. (1)

In the western world, mental illness is ranked as the third most common medical disorder after coronary heart disease and cancer and, together with stress-related disorders, is fast becoming the number one issue of concern for all medical practitioners in the 21st century and beyond unless something is done now.

According to the 1986 edition of Maxcy-Rosenau Public Health and Preventive Medicine on page 1344, it states that:

"A rising pandemic of chronic disease - a large proportion of which is chronic mental disorder and impairment - is producing a major crisis in all public health work."

Reporter Leah De Forest commented that in one particular form of mental illness known as depression, the disease has become an "epidemic":

"....We are seeing an enormous surge in this disease of the mind, with all its wretchedness, and it is being called an epidemic. The World Health Organisation has estimated that by 2020, depression will be as big a burden on world health as heart disease. In Australia, it is the fourth most common ailment that doctors encounter." (2)

What are governments doing about solving mental illness?

As of 2005 in Australia, not much.

Keith Wilson, chairman of the Mental Health Council of Australia, tried desperately to convince Australian Health Minister Mr Tony Abbott of why the government should do more to help people affected by mental illness. While speaking at a conference attended by Mr Abbott, he spoke frankly about his son's affliction with schizophrenia. He said he wanted to find help for his son at a time when his son had turned increasingly violent, attacking his brother and damaging property:

"For 20 of those we found it impossible to find and access appropriate care and intervention for him. I was angry about the system's failings. I was really angry and my anger has never abated, that's what drives my advocacy.

'The appalling state of mental health services is a national crisis and demands a national response....Bring us in from the cold, help us to become real participants in Australian society, don't leave us as the lepers of the 21st century, untouchable, untouched.

'Minister, we look to you and your cabinet colleagues, and especially the Prime Minister, to really listen to the thousands of voices in this report [titled Not for Service]. I know, minister, that you're a man who takes a high moral position as a Christian believer...this situation is actually immoral. We have an immoral disregard for the lives of millions of Australians stricken through no fault of their own and stigmatised and left out." (Price, Matt. Our mentally ill can no longer be ignored: The Weekend Australian. 22-23 October 2005, p.20.)

On hearing this, Mr Abbott argued the only thing he could do was wait for the state governments to relinquish their powers to the Commonwealth. Until then, his hands are tied as we were told.

In the meantime Mr Abbott could not find a couple of hundred thousand dollars to fund an important internet site for depression suffers until eventually he was thoroughly embarressed on radio by influential broadcaster Alan Jones. As Mr Jones put it to the Health Minister:

"You're fiddling and arguing over a couple of hundred thousand dollars. I wish the same kind of scrutiny applied to the hundreds and hundreds, and hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars, Tony, that goes everywhere else. I think it's an absolute disgrace...there is more to life, Tony, than industrial relations legislation." (Price, Matt. Our mentally ill can no longer be ignored: The Weekend Australian. 22-23 October 2005, p.20.)

Within a week, Mr Abbott eventually conceded the web site should be funded and he may contemplate a possible takeover of the health sector to solve some other major problems. At the same time, Prime Minister John Howard was stirred into action by sitting down with state premiers to discuss the problem.

But only if the fundamental causes for mental health are properly acknowledged and solved (which may mean a change in the way society is progressing and behaving). And that includes a thorough understanding of what it means to be mentally ill and what is really happening in the brain to create it. (3)

After 2007, Professor Patrick McGorry from the Centre for Youth Mental Health at the University of Melbourne received much needed funding and support from the Rudd government to help implement a national and integrated mental health care system and apply a new intervention program called ORYGEN to assist young people with mental illness. The essential aim for Professor McGorry is to apply treatment at the moment a mental illness episode commences and to get to the young people as soon as possible before the disease develops any further. Professor McGorry has found the treatment to be most effective and able to minimise the onset of severe mental illness in young people, and especially while the young brain is still developing.

As for the actual reason for mental illness in terms of the mechanism inside the brain, this still remains a mystery.

What do we know about mental illness?

Before this 1986 research study was conducted, not a great deal other than a few common trends.

For example, although mental illness has no barrier to age, race, culture or other social classes, it does tend to peak in the adolescence age (around the age of 14 according to the 1941 study in the United States by the Baltimore's Eastern Health District (4)), and in the old-age bracket (the incidence of mental illness rapidly increases after the retirement age of 65 according to a study of people in a mental hospital in Syracuse in 1952 (5)).

However, one thing is definitely clear - the problem is increasing in numbers and the authorities are looking for answers.

Among the patterns emerging include the nature of modern society in the early 21st century and what it means to live in a rational world run by humans, the rapid pace of change we see in the Western world and the expectations generally placed on people to adapt to this change, the type of foods we produce, the way people's brains develop through life and how we think and solve problems, the focus on money, and the way we show our social responsibility for our fellow human beings.

As the crisis starts to hit hard on our modern society, there is mounting pressure on the authorities to find ways of tackling the problem, from understanding the reasons and causes behind this disease, to ways of preventing it. We need to tackle this problem now because the authorities are realising how the disease is somehow closely linked with many other important social problems of modern society, including chronic gambling and days off work due to stress, to more serious issues such as youth suicide (especially for young males) and crime.

The extreme case of L-brain and R-brain thinking

The latest research from SUNRISE has initially tackled the issue of human behaviour on a general level as part of an effort to understand whether there is any influence of L-brain and R-brain functions on our behaviour.

After a period of time, we noticed how many of the behaviours can be grouped into two categories: L-brain and R-brain. Then we saw similarities in the behaviours to what psychologists call people suffering mental illness but often to a greater extreme.

To see this, let us begin by understanding the general behaviours of mentally-ill patients.

The extreme case of L-brain and R-brain thinking

If one could inspect the behaviours of a large number of patients in mental institutions, we can classify their behaviours into two broad categories:

- Individuals characterised by predictable and very repetitive behaviours such as moving an arm or leg in a rythmic fashion back and forth, and/or repeating a word or part of a word (as if stuttering or chanting a particular sound) over and over again.

- Those individuals characterised by their behaviour as unpredictable and very bizarre in nature such as sudden and uncontrollable outburts for no apparent reason.

When we look back at how the L-brain and R-brain actually works, we discover two interesting facts:

- In the extreme case of L-brain thinking where our analytical mind is unbridled by imagination and visualisation of the R-brain, the consequence on our personality would be in the development of 'cybernetic machine-like' and repetitive behaviours where somehow certain patterns are recalled again and again; and

- In the extreme case of R-brain thinking where the imagination and visualisation is unbridled by the rational mind of the L-brain, this eventually leads to extreme instability and unpredictability in behaviour and thinking.

These extreme L- and R-brain behaviours should give us a clue as to how mentally-ill patients behave. It would appear that the functions of one side of the cerebrum or the other in mentally-ill patients is dominating their behaviour almost completely and, for some reason, there is no mechanism to control this on their own by the functions of the opposite side of the cerebrum (i.e. a lack of application of the frontal lobes for complete thinking and behavioural development).

As further evidence, it is known that locating behaviours which we might classify as abnormal or a form of mental illness in those animals with very primitive nervous systems (i.e. a small cerebrum structure) like fishes are extremely rare.

Dogs and cats with slightly more developed cerebrums are more likely to experience some form of mental illness compared to lesser-developed animals. For example, certain breeds like the Australian Kelpie, a highly active working dog used by farmers, are more likely to suffer bouts of nervousness and possibly more severe mental disorders due to their constant application of problem-solving on the farm such as rounding up sheep and keeping the master happy.

However, when we turn our attention to the human species, the problem of mental illness appears to be much more predominant and one that is increasing over time. Either that, or the media coverage on mental disorders has been far greater for the human species than with other animals.

Why?

The only significant changes that have occurred in the human brain over the past 10 million years has been in the upper areas known as the cerebral cortex, including the frontal lobes. The more primitive areas of the brain - the midbrain and brain stem - have not changed significantly since the days when the first fish walked on land. As author Peter Russell wrote:

"In many respects, the lower parts of our brain and spinal cord have not changed significantly since the time of the early fishes, 100 million years ago."

Could this recent advancement of the human brain in the area of the cerebrum pose the all-important key to understanding mental illness?

Do savants have similar extreme L- and R-brain behaviours?

Where memory is intact and active and can remember specific patterns, a dominant L-brain extracting specific behaviours and knowledge can be remembered. The possibility therefore exists for an individual with this condition to be able to recall many specific facts.

Where the R-brain dominates and the memory is intact, an individual can become a prolific artist drawing a great many pictures or produce music or other creative works.

However, in normal people, the R-brain and L-brain appear to be controlling each other through a healthy corpus callosum and frontal cortex as if the newer part of the brain called the cerebrum is trying to find relevant information in the mass of information stored as patterns in memory. And when relevant information is found and recorded, irrelevant information is removed and forgotten.

Does this mean savants have a lot in common with people having mental illness?

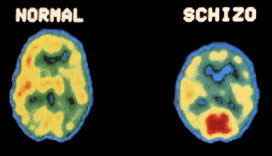

Results of PET scans

If the cerebrum is the area causing problems for mentally-ill patients, then where exactly in the cerebrum is it giving patients and psychologists the real headaches in understanding this social problem?

Perhaps the following Positive Emission Tomography (PET) scans of the brain of a normal person and the brain of a person suffering from schizophrenia may reveal the answer:

These PET scans show clear differences in brain activity, namely in the cerebral cortex region (at the top and bottom edge of the brain), and in the middle of the two cerebral hemispheres (center). Red represents highest electrical brain activity, whereas blue represents the least electrical brain activity.

Notice the reduced brain activity in the middle of the brain of the schizophrenic patient - approximately where the corpus callosum is located which joins the left and right-sides of the brain. Also notice the less activity in the frontal lobes where subconscious thinking, or the manipulation and processing of the L- and R-brain information for long-term and more balanced behavioural and symbolic development, takes place.

Even the overall size of the frontal cortex appears to be small or underdeveloped in the schizophrenic patient compared to the normal patient.

Furthermore, schizophrenic people are more likely to experience visual (and sometimes auditory) delusions than normal people, as indicated by the high amount of brain activity occuring at the back of the head where visual information tends to be stored according to the PET scan of this mentally-ill patient (shown as a large red area at the bottom edge of the picture).

It is possible that schizophrenic patients are still able to think on their own. However, it is probably with great difficulty for the patient because the brain may have somehow compensated for the loss in the frontal cortex by developing in another part of the brain. And it is in this situation where interference with other neighbouring brain functions such as our visual processing centres at the back of the brain which could lead to hallucinations and ultimately mental illness.

Could this breakdown in one part of the brain leading to brain functions developing and interfering in another part of the brain explain things like motor control diseases such as Parkinson's disease? Further research is needed to determine whether this is true.

But most importantly, and this could be the most critical, for whatever reason, the corpus callosum appears to have diminished its responsibility in the schizophrenic patient of shuttling information back and forth between the left- and right-sides of the brain as required for effective thinking, problem-solving and, ultimately, appropriate behavioural changes needed to be classified as "normal" in society.

Remember, the corpus callosum is apparently needed to keep the two cerebral hemispheres from running amok and controlling human behaviour. Otherwise one hemisphere could dominate the behaviour of an individual. It could either cause an individual to become suddenly creative and artistic (R-brain), or someone with repetitive and highly precise skills or show photographic memory skills (L-brain).

Why has the corpus callosum stop its flow of information between the hemispheres? What has ebbed or stopped the flow of information in the schizophrenic patient? It seems that either (i) one-side of the brain or the other has stopped functioning completely (which is not apparent from the roughly equal amount of brain activity occuring on both sides of the brain of the schizophrenic patient); or (ii) the corpus callosum has been damaged sufficiently to affect the flow of information transferring between the two cerebral hemispheres.

Or perhaps the frontal lobes has stopped functioning and hence there is no need for the brain to switch information back and forth between the L- and R-brain through the corpus callosum?

The frontal lobes

There appears to be further evidence to support the possibility that the frontal lobes could be influencing mental illness. A recent study into the brain activities of normal people under the influence of soft drugs such as marijuana show a similar brain scan as above for the schizophrenic patient. The only difference is in the intensity of the active brain areas — often appears to be much less.

Furthermore, once the soft drugs are properly removed from the blood stream and the brain is allowed to resume its normal operations, the active parts of the brain tends to revert back to the normal state.

If, however, the person under the influence of drugs does not give time for the brain to revert to the normal state because of regular doses of the drugs (especially at a young age), the brain slowly realises the frontal cortex cannot function properly. To compensate, the brain tries to develop similar frontal lobe functions in a different part of the brain to achieve its work. The result is a brain learning to interfere with other functions including the visual and auditory regions of the brain.

This is where it is believed schizophrenia develops in the long-term drug-induced person.

So could the frontal cortex be the source of mental illness? Or if it isn't the frontal lobes causing the problem, what about the corpus callosum? How can this create mental illness?

The corpus callosum

If we were to assume for a moment that the corpus callosum has been damaged in some way, what would have caused the damage in the first place?

Perhaps there may be a genetic problem and the corpus callosum did not form correctly at birth. As the 1987 edition of the McDraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, Volume 10, page 593, states:

"Some [types of mental illness] are inherited, others acquired....Some begin at birth or soon thereafter and last for the lifetime of the individual; others appear for the first time during adolescence or adult life and may be cyclical or persistent."

However, there is another factor to take into consideration. We can see what this factor is from the above quote and by looking at the general history of mentally-ill patients. It appears that at or near the moment when their behaviour suddenly turned to the worse, they had been (i) experiencing some form of extreme stress; and (ii) they received limited support and resources to deal with their problem at the time.

One of the most common statements made by family members or friends who knew the patients well is how often the patients received poor emotional and/or physical support (e.g. time, money, love, education and/or other resources) at crucial moments in their life to help get them through an extremely stressful 'problem-solving' period. Perhaps the patients did not receive the love and attention they needed from others? Or maybe society decided it was too hard to support their needs?

Whatever the situation, it seems the patients had a problem and they wanted to solve it as quickly as possible despite the limited support structures available in the environment.

According to the 1998 edition of Comprehensive Clinical Psychology, Volume 6, page 521, the following poor support structures may have been in place for mentally-ill patients:

- Lack of, or poor education (e.g. basic literacy, numeracy and self-help skills);

- Lack of, or poor financial support (including money management);

- Lack of, or poor housing (i.e. poor quality or unstable);

- Lack of, or poor social supports;

- Lack of, or poor levels of occupation/employment;

- Difficulties with close personal relationships (family etc).

Unfortunately, this poverty of or poor support given to the individual combined with the continual self-analysis in the patients' mind to find a solution to their continually stressful problems may have risked, at one particular moment (or a series of them over a long period of time), permanent damage in the region of the brain we suspect is probably causing the real problem behind mental illness, namely the corpus callosum (which leads to reduction in frontal cortex activity and ultimately affect other parts of the brain). (8)

And once this damage occurs, it would probably make it hard for the brain to develop its frontal cortex for effective thinking and problem-solving unless it can find a way to compensate for this (and so risk developing other forms of mental illness such as schizophrenia).

The damage to the corpus callosum probably also occurs when a large amount of information flows through it during problem-solving/thinking. At first, the information flows in one particular direction from one cerebral hemisphere to the other for a fairly long period of time (because of our tendency for one-sided thinking as being the easiest), then suddenly, at some extreme moment of stress or intense problem-solving activity, the brain suddenly decides to reverse this flow of information (perhaps as required for the brain to find a solution and one which will help the brain act more as a parallel-processing device where it can perform several functions involuntarily rather than doing many things consciously). Unfortunately, the nerves for transferring the information in the reverse direction (or the blood vessels supplying the required oxygen and other nutrients to the appropriate nerves) were probably not prepared for this, and the result may have been permanent damage to those nerves.

Nerves cells can die when blood vessels burst under extreme pressure due to extensive nerve cell activity (and/or weak blood vessels structure). When blood vessels burst forming what are known as tiny strokes, nerve cells are starved of their oxygen and this results in their death. This is also thought to be the cause for dementia (9) as well as mental illness.

Therefore, it is likely the problem of mental illness may be more than just a question of genetics. The environment may well play a significant role in the disease.

The environmental influences to our brain

If this is true, and the lack of or poor skills, emotional development and knowledge in individuals to handle certain difficult and/or unfamiliar problems and/or the lack of or poor support structures available in the environment to help people solve the problems is contributing to mental illness, could our modern society be causing more and more healthy and normal people to become mentally unstable?

Could modern and technologically-advanced western society we live in be pushing many of its people to think and behave in one particular way or the other for a prolonged period of time to the point they believe this is how problems should be solve, and then expecting them to solve any highly intense and stressful problem (perhaps in an area not familiar or well-trained in) in a short space of time without adequate rest, training and other forms of support?

If this is true, could there be a link between stress in modern society and mental disorders?

Well, let us find out.